State and its pillars

NOW that the 27th Amendment has been passed, some in the legal profession and others are mourning the new subservience of the judiciary, going as far as to say that the third pillar of government has come crashing down.

Of course, what is less mourned, perhaps, is that the second pillar, parliament, is no longer standing upright either. Having been weakened over the years, it no longer functions as an independent branch either. It sits, stands and runs around in circles on cue — from the leadership of the political parties and the known unknowns. There were hints of it during the passage of the 18th Amendment but the slide began in earnest later — from the lightening-fast approval given to Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa’s extension to the present when constitutional amendments are passed within days. The ‘public representatives’ are led by the Pied Piper to the ‘ayes’ gallery when the vote is needed and there is little choice in the matter. And it doesn’t matter if they are sitting on the treasury benches or are in the opposition.

The executive may have had its hand strengthened by the recent legislation, but simply on paper. But its ability to make decisions is now a thing of the past. The only reason it is perhaps not discussed much is that its helplessness is hidden behind closed doors. In private rooms, it is hard to say who is chairing meetings or making the decisions. The capitulation is just not as public as in the case of the legislature even though the results are visible to all.

Indeed, there is little hope that any of the three pillars of the state are intact.

There is little hope that any of the three pillars of the state are intact.

But in the land of the pure, political theories remain just that — theories. Here, the pillars of the state weaken and crumble, straining just to stay upright but in our everyday lingo, the word ‘state’ is used to denote our respect and our acknowledgement of the power and influence of one institution. At times, we use the word also to concede our own vulnerability. But that is another story.

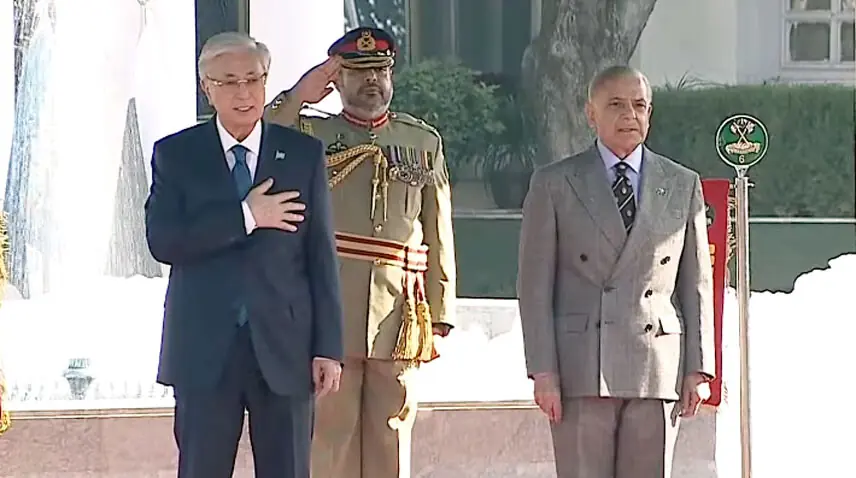

The state hasn’t been left untouched either. The 27th Amendment has brought sweeping reforms to the structure of the armed forces as well. Among other things, the new legislation has discontinued the joint chief position and introduced a new CDF, a position which will be held by the chief of army staff, who now appears to be far more than the ‘first among equals’. At the same time, the tenure of all services chiefs has been increased from three to five years. The head — COAS/CDF — has also been given lifetime immunity, like the president.

It is being said this will help prepare the armed forces for modern warfare and allow for the kind of coordination that was perhaps not possible earlier. Time and again, those who claim to understand how warfare works argue this, but their language explains little to those of us not in the know. These new changes will bring or improve combat readiness, synergy, multi-domain integration — though what this means in practical terms remains unclear to those of us who have never worn a uniform.

It is easier, however, to understand the far simpler concerns or worries that are being put forward.

There are fears that these changes may allow for centralisation of power in a single post/individual that is also above the law. Of course, some can argue that strong men who claimed to speak for or on behalf of the state were always above the law — the trial of Musharraf is a case in point — but now this has been put down on paper. But in a country such as Pakistan where checks on the ruling elite have always remained weak, the precedent being set by offering immunity to any government official is worrying. Others will want to follow suit in the future, as it will encourage decision-making without any fear of accountability.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, questions have been raised about what this will mean for the other two forces and their ability to make decisions or have their views heard if the perception of equality between all three forces is not acknowledged on paper. This, it is feared, will impact not just the morale but also decision-making.

How will it impact decisions about resource allocation, or decisions taken during times of conflict? Will the other services chiefs still be able to make their voice heard, ask some? Here, some insiders have mentioned the 2019 skirmish with India where they claim the then chief of army staff was outvoted when deciding the response to India. This account has been questioned, but as an anecdote it does urge more clarity on how decisions will be made. Will collegial decision-making, which some say has been at work till now, continue once the new structures are in place?

These questions are being asked partly because there is no transparent debate on the changes. If the discussions were open, such questions would not fester.

But beyond the powers, in Pakistan, there is always the worry about how the politics of any changes will play out. A case in point is the frenzied politicking over key non-political appointments as we have seen in the recent past. And one wonders that if powers are further centralised in new positions, whether it will encourage newcomers and aspirants to lobby in new and more aggressive ways for key positions as well as exceptional promotions. The long-term impact of this will not just weaken civilian actors and institutions; this is not one-way traffic.

In a fast-fragmenting state and society where legislation is being used to hollow out institutions such as the judiciary, any new factors that can further add to centralisation of power and increased politicking should worry us all — till some solid answers are provided.

The writer is a journalist.

Published in Dawn, November 18th, 2025