Email reveals he was receiving detailed intelligence briefings on Taliban leadership crisis after Mullah Omar’s death

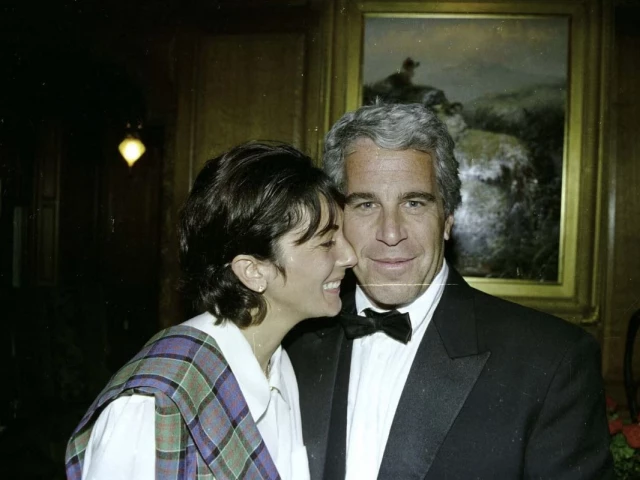

An undated photo shows Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. The photo was entered into evidence by the US Attorney’s Office on December 7, 2021 during the trial of Ghislaine Maxwell, the Jeffrey Epstein associate accused of sex trafficking, in New York City. PHOTO: REUTERS

Among the thousands of documents emerging from the Jeffrey Epstein saga, two emails from 2013 and 2015 stand out for their unusual subject matter.

Far from the financial dealings and social connections that have dominated headlines since the American financier’s 2019 arrest on sex trafficking charges and subsequent death in custody, these communications reveal Epstein operating in Pakistan’s tribal areas, working on polio eradication while receiving detailed intelligence briefings on Taliban leadership dynamics.

The correspondence, involving Epstein and figures including Boris Nikolic, his science advisor and an associate to Bill Gates, paints a picture of operations that blur the line between humanitarian work and intelligence gathering in the volatile Pakistan-Afghanistan border region during a critical period of the War on Terror.

One email in the chain references someone named “Bill” who had “raised all money for Polio,” which may refer to Bill Gates, whose foundation has been a major funder of global polio eradication efforts

The jihad capital of the world

In May 2013, as Pakistan prepared for national elections amid a backdrop of Taliban violence, Epstein was in Peshawar. In an email to Nikolic dated May 1, 2013, Epstein described leaving the city he called “the jihad capital of the world,” apologising for his silence due to “constant bombings in and around town, pre-elections turbulence.”

Email from Jeffrey Epstein to Boris Nikolic dated May 1, 2013. PHOTO: United States Department of Justice

The email revealed an extensive operation.

Epstein claimed to have met with representatives from each of Pakistan’s seven tribal agencies – semi-autonomous Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) that served as Taliban and Al-Qaeda strongholds. He met with the FATA secretary health and the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa secretary health, with whom he claimed to have previously worked “in peacekeeping in Kosovo.”

Pakistani security personnel, who Epstein noted “are based in everrry hotel lobby,” questioned his activities. According to his account, his “Paki name and the subject of polio disarmed them.” The reference to a “Paki name” suggests Epstein may have been using an assumed identity or cover story during these operations.

Most significantly, Epstein wrote that he “managed via Fixer to speak on cellphone to a senior Taliban guy about their position on polio.” This direct communication with Taliban leadership, facilitated by an unnamed intermediary referred to only as “Fixer,” raises fundamental questions about the nature of Epstein’s work in the region.

Behind the polio campaign: money and influence

Epstein’s analysis of Taliban resistance to polio vaccination departed sharply from conventional narratives. Rather than religious objection being the primary barrier, he wrote that “religion-based refusal is a very tiny part, the rest is pressure tactics, one-upmanship, and the vast amount of jobs & money involved.”

This assessment suggests a sophisticated understanding of the political economy of the tribal areas, where control over international aid programmes represented significant power and patronage opportunities.

Read: The Epstein saga is far from over

On the funding front, Epstein reported major developments. “FATA about to sign MOU with UAE Govt, which will give a huge grant covering all polio vaccination campaigns 100% for the next 3 years!” he wrote.

The email chain also contains a cryptic exchange with Boris Nikolic, who wrote: “BTW – Bill raised all money for Polio. Even more than he needed. Can you imagine with your mechanism?” The reference to “Bill” and “your mechanism” remains unexplained, but suggests Epstein’s role extended beyond field operations to fundraising or logistical coordination.

The intelligence briefings: inside the Taliban succession

If the 2013 emails raise questions, an August 2015 email answers them more definitively. By this point, Epstein was receiving detailed intelligence briefings on one of the most sensitive geopolitical situations in South Asia: the succession crisis within the Taliban following the death of Mullah Omar.

Mullah Omar, the one-eyed cleric who founded the Taliban movement in 1994 and led it through its rule of Afghanistan and subsequent insurgency, had died. His death, kept secret for two years, created a leadership vacuum that threatened to fracture the movement.

The August 10, 2015 email to Epstein, sent by Nasra Hassan who was associated with the International Peace Institute (IPI) to Director IPI Vienna, Andrea Pfanzelter, with Advisor for Polio Eradication and Peace & Health IPI, Michael Sarnitz copied, provided the kind of analysis typically reserved for intelligence agencies or high-level policy advisors.

Email briefing situation in Afghanistan dated August 10 2015. PHOTO: United States Department of Justice

The briefing assessed that Mullah Akhtar Mansour, who had effectively been running the Taliban’s military and political operations through the Quetta Shura for five to six years even before Omar’s death, “appears to be gaining ground” in the succession struggle. The document noted that pro-Mansour voices “outweigh the anti-Mullah Mansour voices” and carried “far more weight.”

Among the key figures supporting Mansour was Maulana Samiul Haq of Pakistan, described in the briefing as “the teacher of the majority of the Afghan Taliban leaders at his madrassa, including Mullah Omar.”

Read More: Epstein files reveal damning secrets of global elite

Significantly, Haq was characterised as “pro-PEP” – supporting the Polio Eradication Programme – suggesting the programme’s entanglement with Taliban politics ran deep. The briefing noted that then-Afghan president Ashraf Ghani had “sent him an emissary to intervene” in the succession matter.

The document identified Sirajuddin Haqqani, leader of the Haqqani Network designated as a terrorist organisation by the United States, as one of Mansour’s respected deputies, and concluded that “there is no other senior figure who poses a serious challenge to Mullah Mansour.” Mansour’s succession would face initial resistance from Mullah Omar’s family members before they eventually pledged allegiance in September 2015.

The mechanics of Taliban legitimisation

The briefing detailed the elaborate efforts to legitimise Mansour’s leadership.

To address concerns about the small size of the group that had initially nominated him as Mullah Omar’s successor, the document stated that “a large gathering of clerics is expected to meet (& voice support for him) – right now all efforts are geared to getting this large group safely in one place – no easy task, given the security situation as well as AA/Northern Alliance/NDS forces targeting groups which gather to pledge allegiance to Mullah Mansour!”

This passage reveals the violent contestation around Taliban leadership, with Afghan government forces (referred to as AA/Northern Alliance) and the National Directorate of Security (NDS) actively targeting gatherings of pro-Mansour clerics.

The briefing also tracked developments within the Taliban’s political apparatus. While Mullah Tayyeb Agha Mutasim, head of the Political Office in Doha, had resigned, “he has been replaced by his deputy Sher Abbas Stanekzai” who had accepted Mullah Mansour’s leadership – suggesting the Doha office, which had been engaging in peace talks, would remain under Mansour’s control.

The great game continues

Perhaps most revealing were the briefing’s assessments of great power maneuvering. The document described ongoing US drone operations in both FATA and across the border in Afghanistan, targeting “Afghan Taliban, TTP/Daesh & other militant groups, including the Haqqanis.” It noted that the US “would like the Rounds to proceed & begin to yield results before Prez Obama’s term ends” but were “simultaneously miffed as to why ISI did not support ‘their’ Doha process.”

This reference to competing peace processes – one allegedly backed by Pakistani intelligence (ISI) and another by the Americans through Doha – captures the fundamental tensions in Afghan peace efforts.

The briefing stated bluntly that Pakistani security forces “are still in control of the process” despite the succession complications, and were “very active in trying to get all their chickens in one coop.” It indicated that “both Pak forces as well as the US are keen to stabilize Prez Ghani” while no date had been fixed for “Round 2” of negotiations.

Tellingly, the briefing concluded with a reference to “PEP” (Polio Eradication Programme), noting that “violence & insecurity affect PEP delivery in the field and the attention of the Kabul authorities is focused elsewhere.” The casual inclusion of polio programme updates within a high-level intelligence briefing on Taliban succession underscores how deeply intertwined the humanitarian effort had become with intelligence operations.

The question of cover and purpose

The emails raise a fundamental question: was Epstein’s polio work genuine humanitarian effort that happened to provide access to sensitive locations and information, or was the humanitarian work itself a cover for intelligence gathering?

Epstein, despite having no public health background or official government position, cultivated relationships with scientists and positioned himself as a patron of cutting-edge science and global health initiatives. His unexplained wealth, connections to powerful figures in politics and intelligence circles, and the questions that continue to swirl around his activities have made every revelation from his archives a subject of intense scrutiny.

Also Read: Jeffrey Epstein denied he was ‘the devil’ in video from latest file dump

The correspondence reveals a pattern that extends beyond typical humanitarian operations. The depth of access to Taliban leadership, the sophistication of the intelligence analysis he received, and the operational security measures employed all point to activities within an intelligence framework rather than adjacent to it.

The emails leave numerous questions unanswered. What was Epstein’s actual role in polio eradication efforts? Who was he working for or with? What was the nature of his relationship with Pakistani and possibly US intelligence services? Why would someone with no public health background or official position be receiving sophisticated intelligence briefings on Taliban leadership dynamics?

Perhaps most fundamentally, what do these emails reveal about the intersection of humanitarian work, intelligence gathering, and private influence in one of the world’s most strategically sensitive regions during a critical period of the War on Terror?

As more materials from Epstein’s archives surface, these questions may find answers. For now, the emails stand as evidence of operations in Pakistan’s tribal belt that blur the lines between public health, intelligence, and private intrigue – a reminder that in places like the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region, nothing is quite what it seems, and the boundary between humanitarian and intelligence work can become dangerously indistinct.