Misplaced priorities

EXTERNAL overreach and internal underreach have long characterised the approach of governments in the country. Pakistan’s history bears testimony to a phenomenon that has seen ruling elites focus more attention and energy on external engagements rather than on fixing perennial and mounting problems at home. Preoccupation with foreign pursuits has translated into less concentration on domestic challenges — as if the former can substitute for the latter.

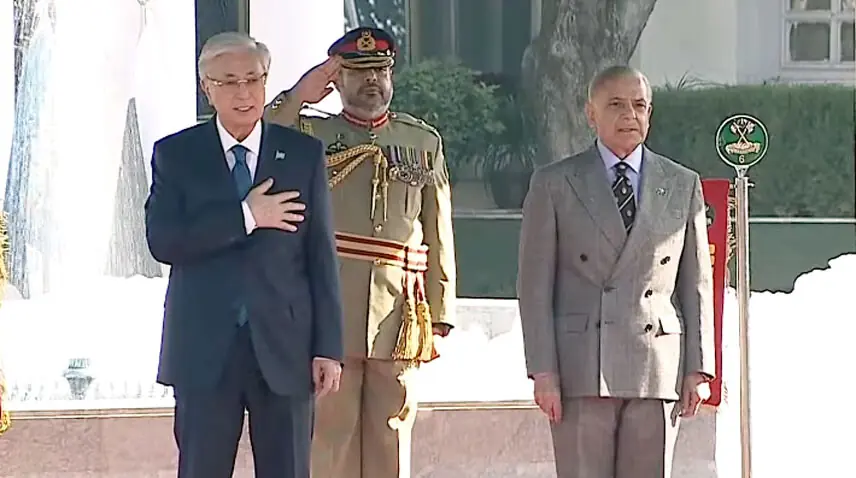

Today too this stands out in sharp relief, as evidenced by the inordinate time spent by Pakistani leaders on foreign trips, regardless of pressing issues at home. For example, during the floods earlier this year that especially hit Punjab, the prime minister spent more time overseas than at home visiting the affected areas. More recently, he chose to preside over a cabinet meeting to approve the 27th Constitutional Amendment — no ordinary piece of legislation — by video link from Baku, where he was on a visit, which was hardly crucial.

Supporters of the government justify these more-than-frequent overseas visits as indicative of Pakistan’s renewed prominence on the international stage, attributing this to the effectiveness of the government’s foreign policy. But foreign policy gains are measured by outcomes, not activity. The real test is whether that delivers anything substantive to the country, and not the number of foreign visits undertaken by a leader or how he personally benefits from such tours. This is not to say Pakistan should not be diplomatically active. But diplomatic engagements should be purposeful and result-oriented, and not take priority over unaddressed governance issues at home.

External overreach and internal underreach have long characterised the conduct of governments.

External overreach and internal underreach has a long pedigree in the country’s history. The origin of this repetitive pattern lies perhaps in the exigencies of the early chaotic years of Pakistan’s existence. In the turbulent aftermath of partition and early conflict with India, Pakistan was faced with a hostile neighbour and its ever-threatening, aggressive posture. This urged Pakistani leaders at the time to pursue a strategy of ‘external balancing’ to counter India’s power by seeking foreign alignments.

This, of course, made perfect sense. It also did not distract the leadership in the formative years from addressing urgent domestic challenges because creating the governance and military structures of a new state and dealing with the huge refugee influx could hardly have been postponed. Nevertheless, Pakistan’s internal political evolution and foreign policy were greatly influenced by its quest for security. And it remained so for years to come.

However, two things happened over time. Prolonged and intense engagement in Cold War conflicts and involvement in later geopolitical developments aimed at strengthening the country’s security ended up emaciating and exhausting Pakistan and compounding its domestic problems. For example, Pakistan’s intimate decade-long involvement in the US-led war against the Russian occupation of Afghanistan — a war of unintended consequences — came at an extraordinary cost to the country’s own stability. Its multidimensional fallout, whose ramifications are even felt today, needs no reiteration.

This also established a pattern of behaviour that was to resonate in subsequent years. While the country’s rulers involved themselves in geopolitical games that sought to enhance Pakistan’s international influence, at home the neglect of pressing economic problems as well as the education deficit exacted a heavy price. Again, the argument is not that Pakistan could have isolated itself from global and regional developments and avoided foreign engagements, but that its leaders failed to anticipate their consequences while paying little heed to festering internal problems.

Policies of external overreach also encouraged a habit of relying on outsiders to address economic challenges. Economic and military assistance or geopolitical rents received through various phases of the country’s alignment with the US-led West created an official mindset of dependence. This set up perverse incentives for domestic reform. Aid and financial ‘drips’ from allies substituted for reforms that could have placed the economy on a sustainable high-growth trajectory and transformed the country.

It also yielded an approach that looked outside to deal with mounting problems and address sources of the country’s internal weaknesses.

The foreign policy of successive governments intersected with their economic management approach by which the country pursued rent-seeking relationships with big powers, relying on aid and borrowing rather than finding a viable path to economic growth and development by counting on itself. But neither foreign assistance nor borrowed money had a transformative impact.

In recent years, reliance on the West has been replaced by dependence on China and Saudi Arabia as well as the Gulf states, who have repeatedly provided financial help to bail out the country from economic and liquidity crises. Roll-over of loans and deposits in the central bank to shore up foreign exchange reserves remains a familiar feature. The habit of depending on others has become so entrenched in the country’s political culture that there is little questioning of this when members of the ruling elite routinely visit Gulf capitals to seek financial help. Instead, ministers hold this up as a foreign policy achievement. If this strategy was followed by an individual would that person be cheered for going out to get more loans when already in debt?

This strategy of reliance on external financial resources has helped civil and military elites to perpetuate their power, privileges, and lifestyle at the expense of the country’s development. It has enabled them to avoid reform while keeping the economy afloat, frequently on life support either from the IMF or ‘emergency’ loans from ‘friendly states.’

What has suffered grievously from neglect are various dimensions of human development and human welfare, which have deteriorated over time. The dismal state of literacy, education and healthcare as well as the rising level of poverty presents a grim picture today, and is the most serious consequence of internal underreach. What value do foreign engagements have when, as a result of official neglect, the condition of the majority of people doesn’t improve and Pakistan makes little progress?

For all the present focus on the ‘external’, the factors that will shape Pakistan’s destiny lie within and not outside the country. Its future will be determined by choices made at home rather than foreign pursuits.

The writer is a former ambassador to the US, UK and UN.

Published in Dawn, November 17th, 2025