HISTORY: THE FORGOTTEN MASSACRE OF MULTAN

On January 2, 1978, Gen Ziaul Haq’s regime ordered security forces to open fire at workers striking at Colony Textile Mills, Multan, allegedly killing 133 people.

No first information report (FIR) was registered, no civilian trial was held and, aside from a military inquiry whose contents were never shared, a public acknowledgement of this state atrocity has never been made. Instead, what remains is a carefully managed absence from Pakistani history books.

The tragedy that occurred that cold winter afternoon in Multan was a direct response to industrial workers who had emerged as a major political force in 1970s Pakistan.

Following the success of the 1969 students’ and workers’ movement that led to the overthrow of Gen Ayub Khan, leftist politics had strengthened demands for more equitable wealth distribution. During the Ayub dictatorship, state loans given to a small circle of elite industrialists had propped up development statistics but, as wealth disparity dramatically increased, Pakistan’s working class was pushed to economic desperation.

In January 1978, Gen Zia’s martial law regime mercilessly mowed down striking textile mill workers in the ‘City of Saints.’ Till today, the scale of the killings is disputed and no official account exists of what is widely considered the bloodiest massacre in Pakistan’s labour history…

Ayub’s removal and the civil war in East Pakistan, which led to the creation of Bangladesh, forced President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to develop legislation for workers’ rights. In February 1972, his martial law government announced new labour laws for Pakistan.

The military, industrialists and even the politicians who had taken their votes were all alarmed at the strength of consolidated worker power. Bhutto’s labour laws, though flawed, dramatically increased the number of labour unions registered in the country and led to regular strike actions by worker groups over fair pay.

Yet the new labour reforms only existed on paper. Mere months after they came into effect, on June 7, 1972, police killed at least three workers who were protesting against delayed wages by the owners of Feroz Sultan Textile Mills at SITE, Karachi. During one of the funeral processions, police opened fire again, leading to more deaths. Bhutto showed no sympathy, saying the strikers were being manipulated by anti-Pakistan elements.

When Zia took over the country, his martial law framed labour unrest as a threat to public order. This was the most violent act by the state against labourers in Pakistani history — a systematic erasure that reveals the nexus of state-capital power under martial law.

Elite Capture

Understanding the massacre requires understanding who owned the mill — and their proximity to power.

The Colony Group, owners of Multan Colony Textile Mills, exemplified the industrial elite that had prospered under the Ayub regime. With its business primarily in textile manufacturing, this Chinioti/ Sheikh family group had been well-established before Partition and gained considerable strength due to limited competition in the nascent state.

In 1961, the Colony Group was a part of the big five industrial houses, who each held over Rs50 million — a vast fortune by 1961 standards and equivalent to approximately Rs10 billion today, adjusted for an average annual inflation rate of 8.6 percent — in assets. As with the other industrial groups, it benefitted from the establishment of the Pakistan Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) in 1952.

Naseer A. Sheikh, the eldest son of the group’s founder Mohammad Ismaeel, served on PIDC’s Board of Directors. Even after the conglomerate split into two, the Colony Naseer Group, which oversaw the mills, was the seventh richest company in Pakistan in 1970, according to economist Rashid Amjad, former vice chancellor of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

Even after Bhutto started nationalisation in 1972, the Colony Naseer Group — despite losing Rs93.9 million or 49.5 percent of its assets — was the sixth richest industrial house in Pakistan. When the tragedy happened in 1978, 13,000 workers were employed at Colony Textile Mills.

Media Coverage and the State Story

Reporting on the events of January 2, 1978, was carefully managed.

The government-run Associated Press of Pakistan (APP) had been given a handout, and Dawn’s front page on January 3 carried the small headline “Five killed in Multan firing.” International papers reported similar figures, with The New York Times using a United Press International (UPI) wire, stating: “Five Killed and 10 Hurt As Pakistan Police Open Fire at Strikers.”

The French publication Le Monde and British daily The Guardian carried the same number. The Times of India, however, reported on January 4 that “at least a dozen people were shot dead… The death toll may be 50.”

In Pakistan, the APP report framed workers as unreasonable from its opening line, claiming they “refused to accept” a mutually agreed bonus and “proceeded on illegal strike” from December 29, 1977. The APP report of the incident stated that workers had demanded a bonus of four-and-a-half-months’ pay, which the Colony Group management refused, saying as it was “not commensurate with the margin of profit.”

The APP report continued that, on January 2, 1978, the labourers on strike became “unruly and rowdy and thousands of them encircled the police force and started brick-batting, resulting in injuries to eight of the policemen, including one ASI [assistant sub-inspector] and one head constable.”

The report concluded that the police had to react in self-defence against a crowd that could not be managed and had turned violent. “The police was ordered to lathi-charge [baton-charge], which they did, and teargas was also used to disperse the unruly mob.”

Inquiry and Discipline

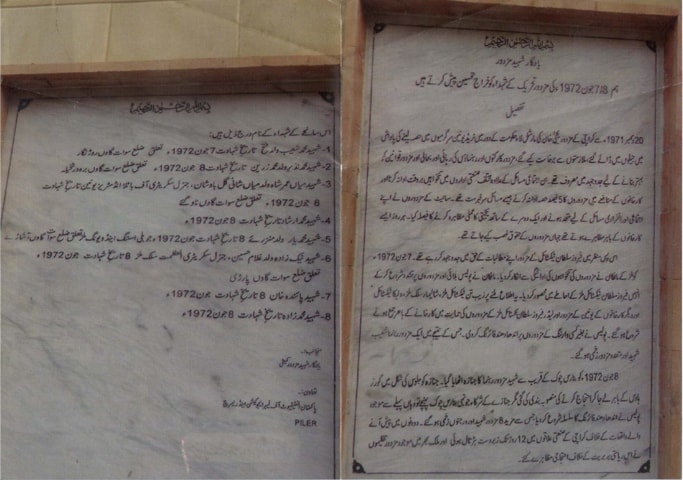

In the following days, swift administrative action was reported. The mill management announced compensation for the deceased and, within two days of the massacre, the martial law administrator (MLA) for Punjab suspended Multan’s senior superintendent of police (SSP), Chaudhry Niamatullah, assistant commissioner (AC) Jam Jan Mohammad, and the area’s station house officer (SHO), Raja Khizar Hayat.

A three-member inquiry committee was also established, with Brig S.M. Ilyas, Col Naeem and Magistrate Sardar Alam, who were going to record “in camera” witness statements. A statement was also taken from Mughis Sheikh, Naseer’s younger brother, who managed the mill.

On January 6, 1978, an “official clarification” was issued, in which the commissioner of Multan Division verified that those killed at Colony Textile Mills “are not more than 14.” This clarification also stated that the number of dead included those whose families had taken them to their villages, instead of the city hospital, “which resulted in their ultimate deaths, as they could not get proper medical aid” — a claim that appeared to shift blame from the shooting to delayed medical care.

Additionally, it reported that the administration claimed it did not bury any bodies, with all of them handed over to their families — a claim later contradicted by witness testimonies.

Even Dawn, in a restrained editorial titled ‘A tragedy in Multan’, could only express that, “It is extremely sad that this major clash should have taken place in the days of a Martial Law regime dedicated to the revival of democratic rule and social harmony.”

Merely 13 days after the massacre, on January 15, martial law (ML) authorities ordered workers to return — framing it as an ‘appeal’. Maj Gen Ejaz Azim, Multan’s deputy MLA, along with other officials, visited the factory and claimed that 92 percent of workers were present and the mills were functioning.

With attention having rapidly shifted to restoring production, workers were promised a bonus equivalent to three months of basic pay on February 1 and recreation allowance on May 1. However, workers were denied pay for the days they were on strike, from December 29 to January 2.

ML administrators were now regularly visiting the factory and, on January 21, Maj Gen Azim addressed workers that Gen Zia himself had expressed “heartfelt sympathies” and gave “assurance that justice will be done.”

BEYOND THE OFFICIAL ACCOUNT

Yet what the martial law administration allowed in reporting differed drastically from what those on the ground — and researchers documenting Gen Zia-era abuses — have recorded.

Gen Zia was close to the Sheikh family, having served as Corps Commander Multan right before his appointment as chief of army staff. He had arrived in Multan on January 2 to attend the wedding of Mughis Sheikh’s daughter. Workers reported hearing that the bride’s dowry was 10 times the amount of the bonuses they had demanded.

According to Hassan Gardezi and Jamil Rashid in Pakistan: The Roots of Dictatorship, workers had occupied the factory floor since December 29, when the strike started, preventing a lockout by the mill management. Aslam Khwaja in People’s Movement in Pakistan writes that, during the afternoon shift-change on the day of the tragedy on January 2, when workers gathered at the gate for a union meeting, police asked them to end the “illegal” strike.

Meanwhile, during the wedding, Gen Zia was allegedly told that workers — having heard of his presence — had gathered in their thousands and were marching towards the event.

What followed next remains shrouded in mystery, even after 48 years: large numbers killed with over 400 injured as, according to news accounts, police opened fire. Those involved in the strike and affected by the incident vehemently argue that Gen Zia ordered troops to open fire on the protesters.

Mystery also surrounds the number of casualties, with figures varying drastically — from state-reported counts of 14 deaths to union claims exceeding 200. The most widely-accepted figure among researchers and labour activists is 133, collated by the Mazdoor Action Committee, which was formed by local labour organisers in the wake of the massacre.

According to political activist and theorist Lal Khan, those desperately trying to escape the bullets were crushed in the ensuing stampede. When the firing began, workers’ families who lived within the mill’s residential compound came outside to get the bodies of their loved ones, but were prevented from retrieving them by law enforcement. The firing continued for three hours; by six in the evening, law enforcement had seized control.

The burial site for such a large number also remains disputed, with testimonies suggesting that some victims were still alive when thrown among the dead. Testimonies available today mention two possible locations: one, a sewage drain where bodies were dumped by tractor; another, a hastily dug ditch. Multiple people in Multan, speaking to Eos on condition of anonymity, said that the bodies were buried so badly that scavenger animals picked at limbs protruding from the ground.

Aftermath and Denial

Soon after the tragedy, the United States Department of State lauded Gen Zia for his human rights record, particularly with reference to arbitrary arrests.

In a report issued even a year after the tragedy, the US state department made no mention of the massacre. Instead, it reported that “The labour movement in Pakistan is limited by the relatively small size of the industrial sector.” The report acknowledged that “Martial Law regulations currently prohibit both strikes and political activity by unions.”

Meanwhile, accounts of the true scale of the violence, contradicting the state narrative, had emerged from Multan. Urdu dailies Imroze and Mussawat had reported the firing, and the editor of Imroze Multan, Masood Ashar, was transferred to Lahore. The Karachi Workers Coordination Committee (KWCC) observed a week of mourning, and also announced that a fact-finding delegation was being sent to Multan.

The Punjab chapter of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) separately announced the formation of a five-member fact-finding committee. Labour unions across Pakistan — including the Muttahida Mazdoor Federation, the National Labour Federation and others — demanded a judicial inquiry.

Journalist organisations also condemned the suppression of accurate reporting. Separately, a meeting of journalists at the Karachi Press Club on January 8 asked for a new inquiry over the police firing at workers in SITE in June 1972, which they suspected was also a cover-up.

Meanwhile, ML administrators were adamant that knowledge of the event be suppressed. Intensifying pressure on workers at the textile mill, on March 12, a summary military court of Multan sentenced three labour leaders for organising a strike on February 16. Wasl Mohammad received one-and-a-half years of rigorous imprisonment (RI) and 15 lashes. Amir Ali and Abdul Khaliq received nine months RI and seven lashes and one year RI and 10 lashes respectively.

No Recognition

Despite the scale of the violence, the state’s grip on affairs in Pakistan was such that no FIR was filed. Outside of the military inquiry, whose contents were never shared publicly, no official account exists. The government has never articulated what exactly happened.

The state has never accepted that the massacre took place.

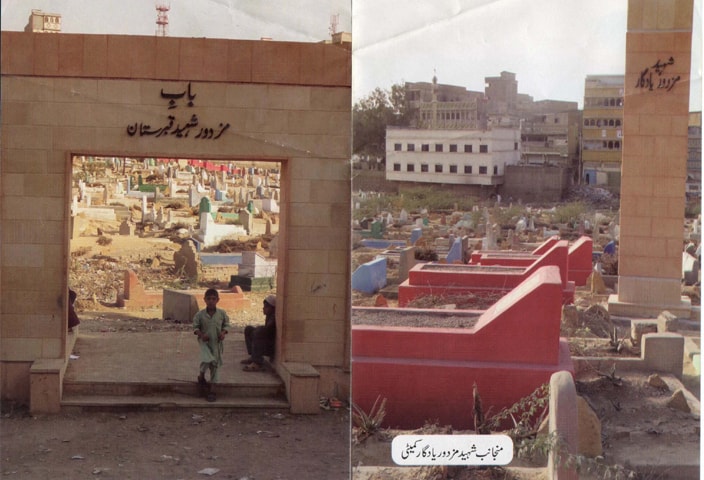

By contrast, the 1972 killings of labourers in Karachi have some recognition. The Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (Piler) erected a memorial in Frontier Colony, Karachi, and the graves of the slain workers are painted red. At Colony Textile Mills, Multan, no memorial exists.

The cruelty of denial is still starkly present.

Mughis Sheikh died in 2024 and former prime minister Yousuf Raza Gilani paid condolences to the family. Meanwhile, workers from January 2, 1978, still await justice and recognition. Yet on Pakistan’s 75th independence anniversary in 2022 , Punjab’s Labour and Human Resource Department awarded Colony Textile Mills a “Best Employer Award.”

This shows that, to this day, state and elite interests remain the same.

But there is a way to dispel this notion: by making public the sealed military inquiry and convening an independent investigation to finally establish what really transpired that day.

The writer is Managing Editor of Folio Books. X: @saeedhusain72

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 18th, 2026