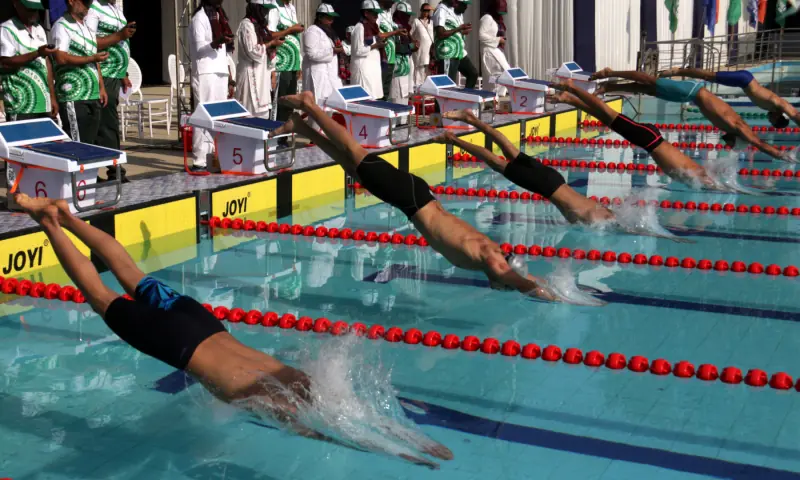

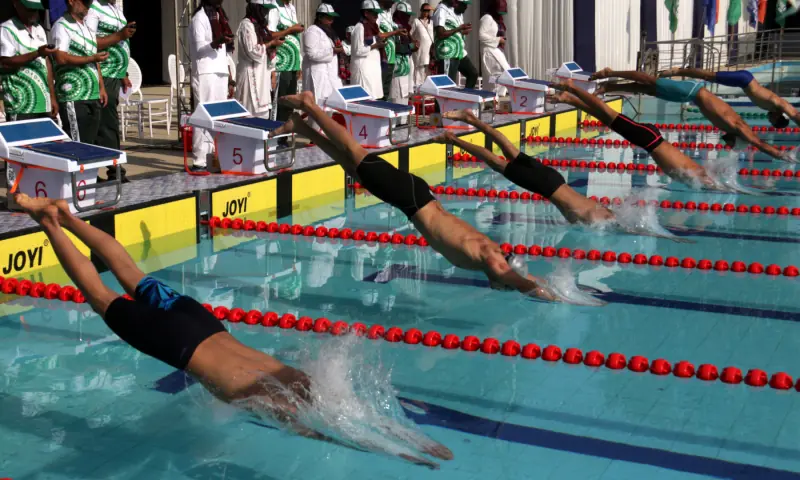

Back to basics: Faulty technical equipment sends shockwaves in National Games pool

It was the late 1990s on a crisp December morning in Karachi, the cloudless blue sky and glossy pool smiling at each other. Swimmers hunched over the edge of the pool before diving in as three technical officials standing behind with manual stopwatches clutched between their index finger and palm. Races concluded and left gold medallists and photo-finishers alike clueless on whether they had set a personal best time or age-group record. They simply had to wait for the results to be announced several minutes later, which translates to eons in the mind of an athlete.

Except it wasn’t the 1990s — it was 2025, and swimming at the 35th National Games embodied the phrase “back to the future”. Sindh had finally caught up to the other provinces and installed touchpads in a 50m swimming pool in Karachi as per rules mandated by the Pakistan Swimming Federation.

But no sooner had the imported touchpads and display boards been installed that they went kaput. Rumours of faulty technical equipment circulating the night before were given merit on Tuesday morning as the display board wilted in the Karachi heat; they were simply not meant to be installed outdoors. Makeshift decorative shades at the KMC Swimming Pool could no longer protect the facade that the long-overdue, freshly-imported, trumped-up equipment was useless.

“How are you conducting something as major as the national games without proper equipment? This is ridiculous,” one mother huffed and threw her hands up as her son was held hostage to the manual timings being announced later.

The women in the morning session were on the luckier side of the malfunction; some races saw all swimmers’ results displayed, others saw the board selectively display a handful of times. By the time the men’s session rolled around in the afternoon, the display board was a blank gravestone at the far end of the pool.

Swimmers even reported feeling mild jolts when they pressed the touchpads, raising questions on the possibility of electrocution in the pool.

However, a Chinese technical aide who had flown in along with the Joyi touchpads told Dawn there was no possibility of that since the battery was only 24 volts.

“I won’t be able to test it, nor can I determine the problem,” he told Dawn through an app that translated Chinese and English speech into their respective scripts.

“Maybe the high temperature caused it to overheat, or the current leakage yesterday caused it to be damaged. We’ll have to test it after the game to know,” he said.

The backup plan to the technical disaster was to revert to manually timing swimmers with three stopwatches. The median time would serve as the official result, possibly half a second slower than the meticulous precision of touchpads.

The issue was the quality of the imported equipment. Joyi would not guarantee the same performance as Omega touchpads, which have loyally served the Pakistan Swimming Federation for 28 years at the Pakistan Sports Complex in Islamabad. Joyi had not lasted even 28 days.

Even the backstroke start ledges imported were an obsolete kind unable to be used in the three days of competition, while the start blocks were flimsy with inconveniently placed touch sensors occupying the surface area of the blocks compared to modern stands having sensors at the side. Where the world was moving towards solution-oriented systems, Sindh swimming was offering a problem-oriented setup to the disadvantage of the swimmers.

The lack of depth in the pools was a mirror image of the conditions outside as officials from the national federation claimed they had not been consulted on what equipment to import ahead of the games, and the absence of quality equipment and collapsing systems was akin to the political systems among the provinces. This was precisely why the national swimming fraternity had lamented swimming being held in Karachi owing to the lack of sporting infrastructure that supported athletes in their peak performance.

The swimmers had advanced, race times have gotten faster, nearly everyone is suited in the latest, most-expensive fastskins, training has become a highly specialised, private venture, but the system in Sindh was still broken — literally.

Even the scheduling of the games in the middle of December was criticised for its clash with end-of-term exams. School-going swimmers mentally prepared at 9am for their races and at 10:45am for O- and A-level exams as they slipped out of swimsuits and into their uniforms.

Even a non-swimming technicality that is the humble victory podium was replaced by a digital counterpart projected on the field behind, as though equality of height were the end goal of this technological experiment.

But the failed frills and thrills at the poolside were a blip for the swimmers. Technological gaffes didn’t stop them from a duel in the pool that ended in high-fives and bearhugs across the lane-line after the race.

The sparse, largely affluent ecosystem chattered in varying American and British accents as dual national swimmers living abroad descended on Karachi to dominate the pools. Younger siblings munched on chips and sipped on Milo boxes being sold outside while the parents fretted over swimmers’ physical recovery and mingled among themselves.

Experience was measured in the length a swimmer spent underwater before surfacing at the start of the race, whether a bronze left them miffed or elated at the cusp of a podium finish.

With two more days of competition left, it remains to be seen whether the technological backsliding will worsen or be resurrected through some miracle.