NATURE: THE MYSTERY OF MIMICRY

Camouflage and mimicry are among the oldest concepts in biology — taught in classrooms as elegant outcomes of natural selection. Animals that blend in avoid getting eaten. Over many generations, tiny random changes accumulate. Simple, neat, intuitive.

But the deeper scientists look, the more the real world looks less like a simple narrative and more like a puzzle with missing pieces.

Across the animal and plant kingdoms, there are creatures whose mimicry is so precise — down to texture, colour gradients, behavioural nuance and even spectral reflections invisible to the human eye — that the standard explanation strains at the seams. What mechanisms allow an insect or a plant with no brain, no eyes and no cognitive awareness of its surroundings to develop such astonishing resemblance?

Take, for example, walking stick and leaf insects. Some species do more than mimic the general outline of foliage; they reproduce irregular edges, asymmetries and colour variations indistinguishable from real leaves — even under close inspection. Predators that rely on pattern recognition walk right past them. The perception of texture and shading that these insects embody is typically associated with sensory and neural processing — yet they lack anything resembling a central nervous system capable of that.

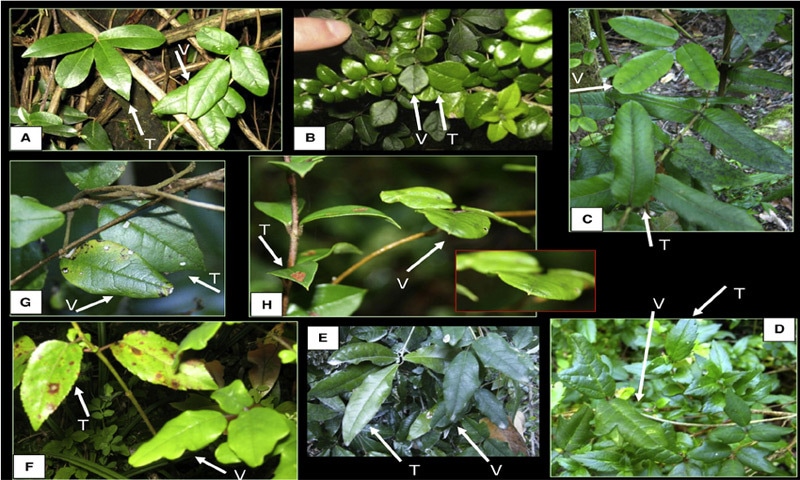

From mantises matching UV patterns they cannot see to vines copying plastic leaves, nature’s most precise disguises challenge simple evolutionary explanations

Or consider moss-mimicking stick insects filmed in South American rainforests. These insects display not just green surfaces but irregular lichen-like roughness and mottling. Their bodies look like small patches of moss clinging to branches. The patterns of light and dark, the uneven ridges and indentations, and the behavioural postures enhance the illusion. All produced without eyes capable of seeing the moss they so closely resemble.

Then there are the orchid mantises, a case that explicitly challenges assumptions about sensory requirements for mimicry. These insects mimic flowers not only in shape and colour but in ultraviolet reflectance — a visual band invisible to humans. Many of the insects they deceive (bees, flies) see this ultraviolet spectrum. But the mantises themselves cannot see ultraviolet patterns. Despite this, their bodies evolve ultraviolet reflectance that matches real flowers so closely that pollinators land on them routinely, mistaking insect for nectar source.

A plant example intensifies the puzzle. In South America, the vine Boquila trifoliolata can grow leaves that mimic the shape, size, colour and venation of nearby host leaves — even when those hosts are artificial plastic cutouts. This suggests that the vine responds to local cues in its immediate environment with astonishing specificity. Whether the cues are chemical, light-based or something else entirely, the mechanism remains unclear. What doesn’t appear to be required is any form of vision or cognition — yet the results are near-perfect mimicry.

Finally, some caterpillars display mimicry so dynamic that it becomes behavioural rather than purely morphological. Certain tropical caterpillars, when threatened, inflate their bodies and rear up in a way that makes them appear strikingly like a small snake. The patterning, the posture, the timing of the display all combine to trigger hesitation in predators that hunt visually. This behaviour — which requires striking precision of posture and display — occurs in organisms with only rudimentary nervous systems.

What unites these examples is not just mimicry but extreme mimicry: cases where resemblance is fine-grained, context-sensitive and effective against the perceptual systems of other organisms. These are not simple cases of “same colour = hidden”; these are examples where texture, shape irregularity, spectral signatures and behavioural display all converge to create illusions that fool highly tuned biological sensors.

Standard evolutionary theory explains the existence of mimicry — that similar forms can be favoured by selection when they confer survival advantage. But in many of these cases, the path from “random change” to “highly specific resemblance” is not clearly documented. Intermediate stages would not function, or would function poorly. Many of these mimetic features appear as if they encode information about the environment that the organism itself cannot perceive.

The accumulating evidence prompts more questions than answers:

• How do organisms without visual systems produce mimicry tailored to visual systems they do not possess?

• What sensory or molecular mechanisms allow plants to adjust leaf morphology to match local neighbours — including artificial proxies?

• Are our explanations too focused on selection after the fact and not enough on how complex phenotypes originate in the first place?

These questions are not a repudiation of evolutionary biology — they are an invitation to expand it. The natural world continues to defy simple explanations, revealing depths of complexity that resist tidy summary.

By confronting these puzzles with honesty, scientists expand both theory and wonder.

The writer is a banker based in Lahore. X: @suhaibayaz

Published in Dawn, EOS, February 15th, 2026