Islamabad’s nights are losing their chill as city’s winter warms up

ISLAMABAD: Winter in Islamabad, which runs from December through February, transforms the city into a serene landscape of quiet, scenic streets and chilly winds.

While the capital enjoys plenty of sunny afternoons, night temperatures frequently drop to between 1°C and 4°C. On rare occasions, a strong cold wave will even leave a delicate dusting of snow atop the Margalla Hills, drawing crowds to catch a glimpse of white-capped peaks.

Over the years, however, winter in the capital has become progressively shorter and warmer due to a combination of global warming and human-induced factors. Weather data from the Pakistan Meteorological Department between 1981 and 2025 shows a noteworthy shift in Islamabad’s climate profile.

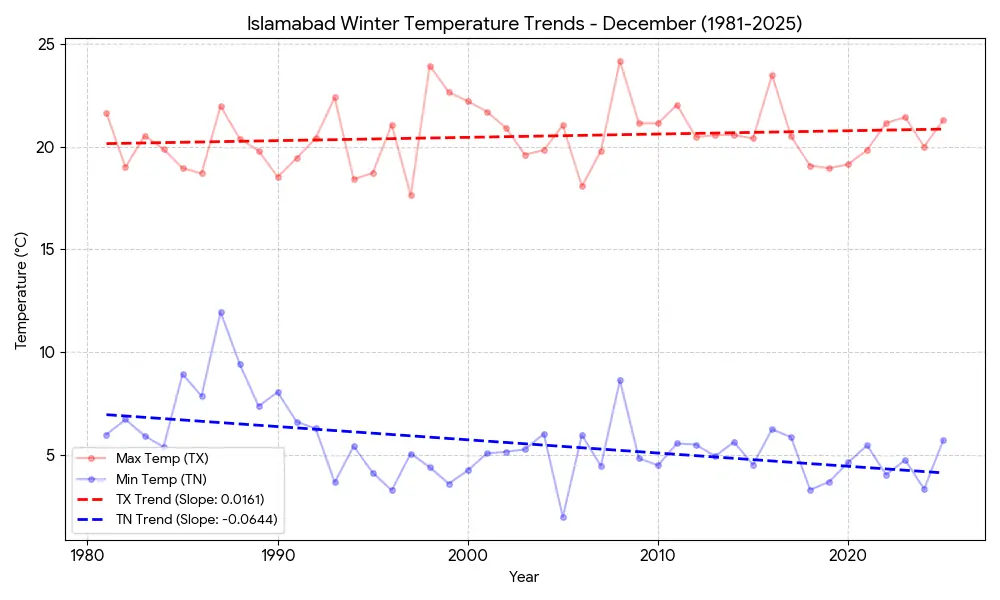

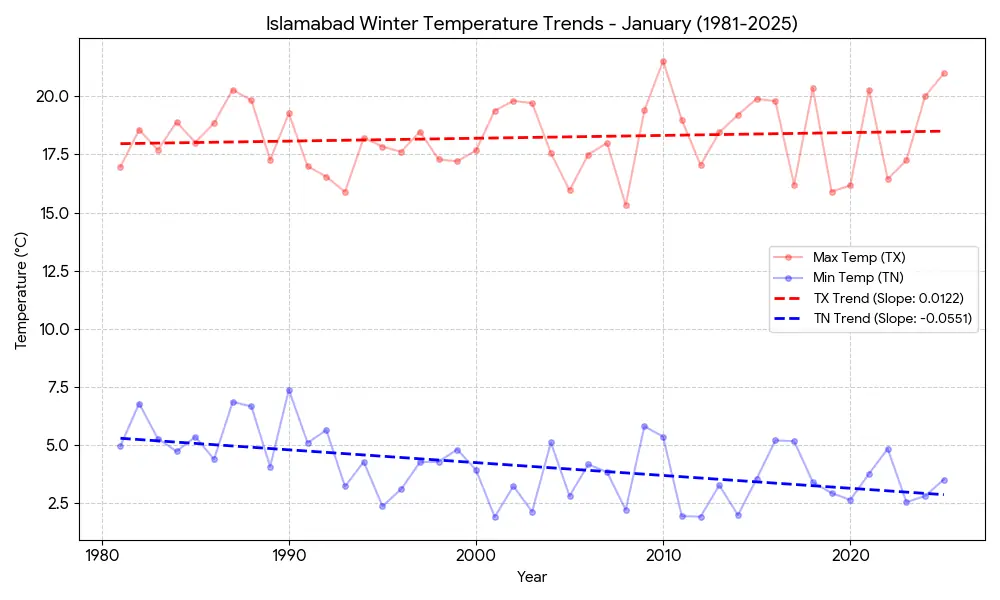

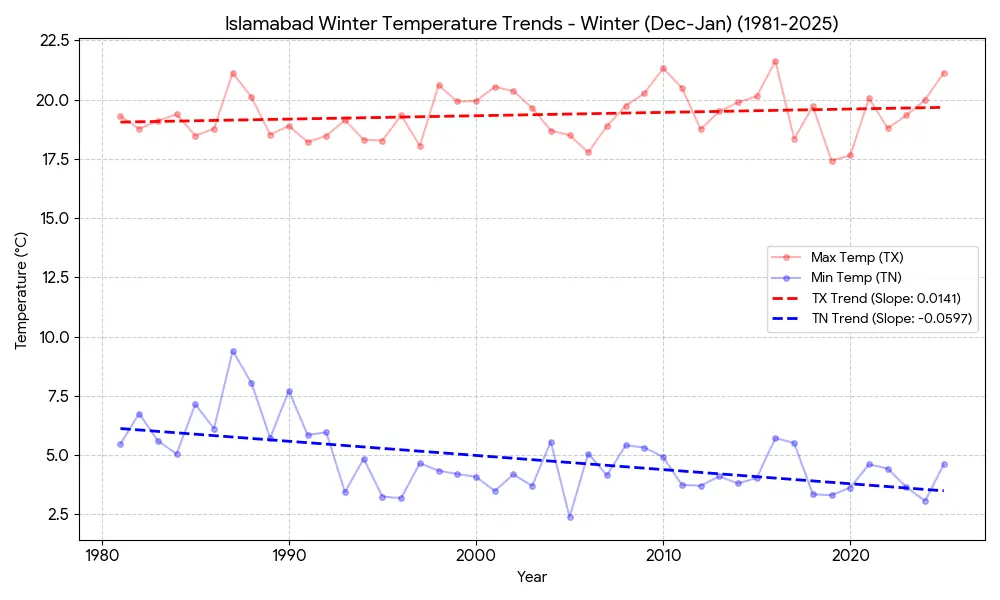

According to an analysis of mean maximum (TX) and minimum (TN) temperatures during December and January, the warming trend is specifically asymmetric. While the overall climate is warming, minimum (nighttime) temperatures are increasing at a much faster rate than maximum (daytime) temperatures.

Danish Baig, the head of Meteorology at WeatherWalay — an Islamabad-based private weather company — described this pattern as widely recognised in climate science as “a strong indicator of anthropogenic climate change”. “[Such a weather pattern] suggests a transition towards a more thermally moderated winter climate regime,” he said. Dawn obtained the dataset from the Met department and shared it with Baig for analysis.

Baig’s assessment has been supported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its 6th report (AR6), in which the leading scientific body noted that the “frequency and intensity of hot extremes (including heatwaves) have increased, and those of cold extremes have decreased on the global scale since 1950 (virtually certain). This also applies at the regional scale, with more than 80 per cent of AR6 reference regions showing similar changes.”

Human-induced greenhouse gas forcing is the main driver of the observed changes in hot and cold extremes, the IPCC confirmed.

It may be noted that the global temperature in the post-industrial age has risen more than the 1°C to 1.5°C threshold agreed under the Paris Agreement has been breached twice – in 2024 and 2025.

According to Baig, the changes in winter temperature reflect the impact of climate change in Pakistan. “The pronounced rise in winter minimum temperatures relative to daytime maxima reflects enhanced longwave radiation trapping during nighttime hours and is consistent with increased greenhouse gas concentrations, elevated aerosol loading, and changes in winter cloud cover,” he said after analysing the dataset.

“This asymmetric warming is a well-documented characteristic of climate change across South Asia and is particularly evident in urban and peri-urban environments,” he said. The expert added that warmer night-time temperatures “reduce the occurrence of radiative cooling, leading to fewer frost events and persistently warmer winter nights”.

He said a similar warming pattern was visible in Lahore and Peshawar as well. Meanwhile, a report prepared by the Karachi Urban Lab, which reviewed a 60-year dataset, reached a similar conclusion for Karachi.

Pakistan Met Department Chief Meteorologist Dr Muhammad Afzaal told Dawn that local factors, particularly deforestation, were also responsible for this “observed rise” in temperatures.

“Climate change drives broader warming trends, with Pakistan’s mean annual temperature rising over a recent decade, prolonging heatwaves and elevating both daily highs and lows,” he said.

Another factor making the city hotter is the urban heat island effect, he said, adding that rapid expansion since the 1990s has “significantly enhanced Islamabad’s urban heat island effect”.

“Increased built-up surfaces, reduced vegetation cover, and continuous anthropogenic heat emissions have particularly amplified night-time warming during winter,” Dr Afzaal said.

“Locally, rapid urbanisation replaces green spaces with concrete, intensifying the urban heat island effect; tree cover has dropped as housing expands, trapping heat and preventing nighttime cooling. Deforestation exacerbates this, reducing shade and carbon sequestration,” he added.

Islamabad’s residents are experiencing firsthand how the winter season is changing around them.

Nasir Jamil, a schoolteacher from Gokina village in the Margalla Hills, told Dawn that the capital city used be colder in the 1980s. He said that some peaks in the Margalla would regularly receive snow in the winter, but he has not seen these snowcapped peaks for a long time.

“There were hardly any vehicles or roads, and the city’s air was pristine, but now, deforestation and infrastructure expansion, particularly in the Margalla Hills area, have taken their toll,” said Jamil.

Climate policy expert Ali Tauqeer Sheikh agreed that winters were getting warmer, saying this was evident even through “observational science”.

“The changes in weather patterns did not occur abruptly, but rather took decades, and the solutions would also need to be tailored, keeping long-term planning and sustainability in mind,” he said.

Sheikh suggested that Islamabad’s urban planning should include more indigenous solutions, such as ‘doongi grounds’ for groundwater recharge. Urban landscaping, he noted, must prioritise plants that are resilient to rising temperatures, have broad leaves to absorb carbon and support local fauna, ensuring that urban plantations can withstand increasing heat.

He added that expanding tree canopies across the city as green ringtones can help reduce the urban heat impact, while minimising asphalt surfaces can decrease water runoff and heat absorption.

Some solutions that can be deployed to adapt to a changing climate include reducing built-up areas where possible, increasing porous surfaces to support groundwater recharge, implementing rainwater harvesting, and designing better storm drains to manage urban flooding, he said.

“One thing is certain: the current developmental model cannot keep pace with changing weather patterns, and policymaking must adapt to reflect the realities of climate change and its effects on urban environments,” Sheikh said.

For adaptation, planting trees is not the answer. It requires local solutions, such as shelters for the poor and vulnerable, Dr Nausheen H Anwar, who heads the Karachi Urban Lab, said.

According to Dr Anwar, the fundamental problem is that extreme climate impacts, including cold and hot, will not cease without risk mitigation, while risk mitigation requires a global-scale intervention to reduce fossil fuel consumption.

Scientists and policy experts have suggested that to protect the public from heat, the government should have a proactive approach in the form of early warning systems, introduce more green spaces, and use innovative techniques, such as coal coatings, to reduce heat absorption. “Adaptation and risk mitigation go hand in hand,” Dr Anwar, however, noted.

Besides making cities hotter, the rising temperatures have broader “environmental and socioeconomic” ramifications.

“It changes winter energy demand patterns, increases winter smog potential, reduces the frequency of frost events, and alters agriculture chilling requirements” across northern Pakistan, according to Baig. “Winter temperature trends in Islamabad, when examined alongside Lahore and Peshawar, reveal a structurally consistent warming pattern across northern Pakistan.”

The impact on agriculture is also confirmed by the IPCC scientists, who warned that fluctuating rainfall patterns and rising temperatures, an effect of global warming, were expected to reduce yields of staple crops in the region.

In an email to Dawn, Dr Mukesh Gupta, science officer of IPCC Working Group II, said that the increased frequency of extreme weather events, like floods, directly threatens crop production and disrupts food supply chains. He proposed crop diversification and climate-resilient seeds, among other measures, to address this looming food crisis.

“Adaptation strategies, including the development and use of climate-resilient seeds, can mitigate some impacts, but financial and technological barriers limit their adoption in low-income countries like Pakistan,” he said, adding that equitable resource use and enhanced access to technology are essential to deal with this problem.

Header image: A view of clouds in the sky during rainy and cold weather in Islamabad on December 21, 2025. — Mohammad Asim/White Star