It took me an hour to write book with AI. Is that a good thing?

It took me about an hour to produce a 50-page-long children’s book. All it required was a handful of prompts to ChatGPT.

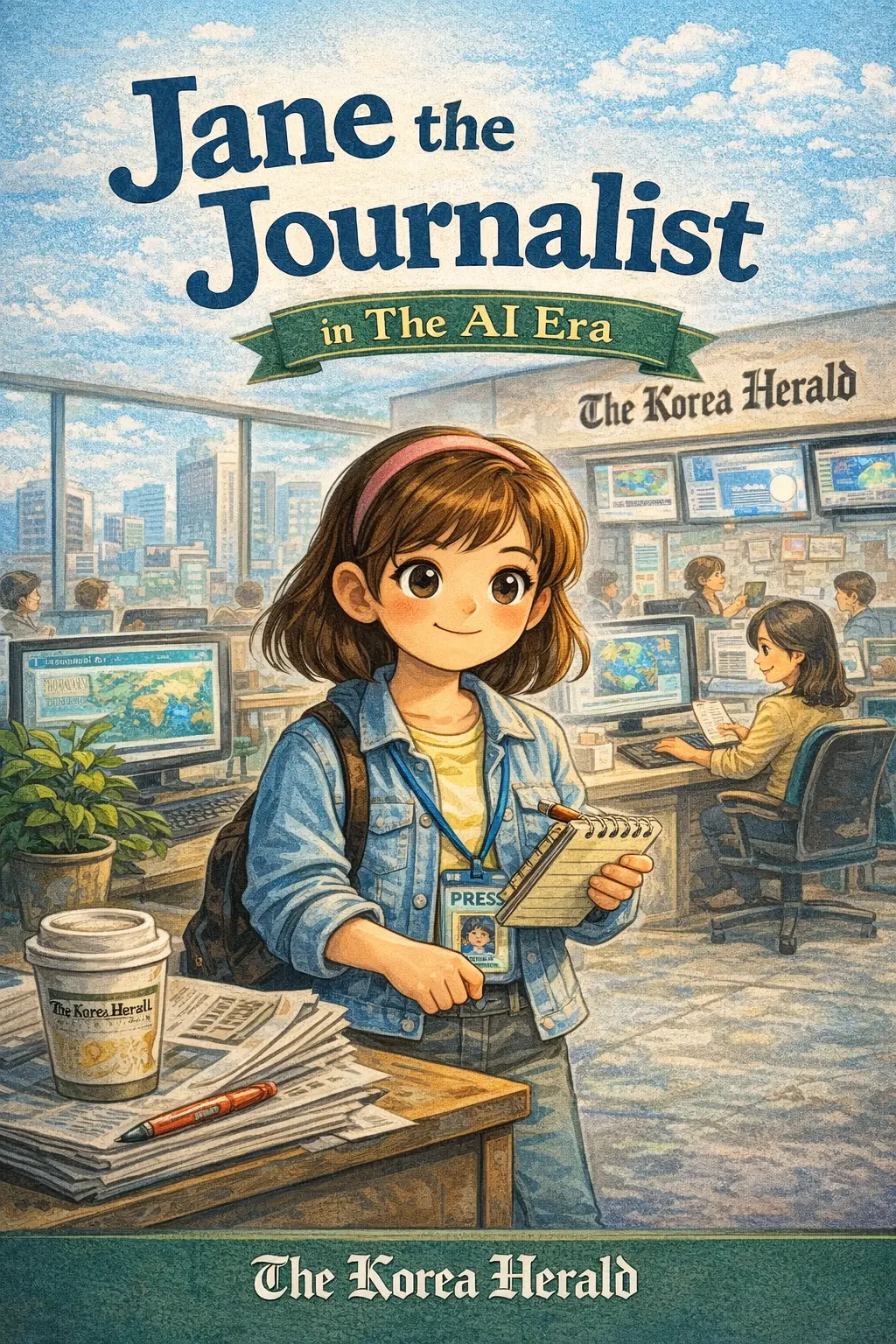

The task was simple: Write a children’s story about a journalist living in the age of artificial intelligence, set at The Korea Herald, with a main character named Jane.

Here’s what I got.

Both the book cover image and the title were created by ChatGPT.

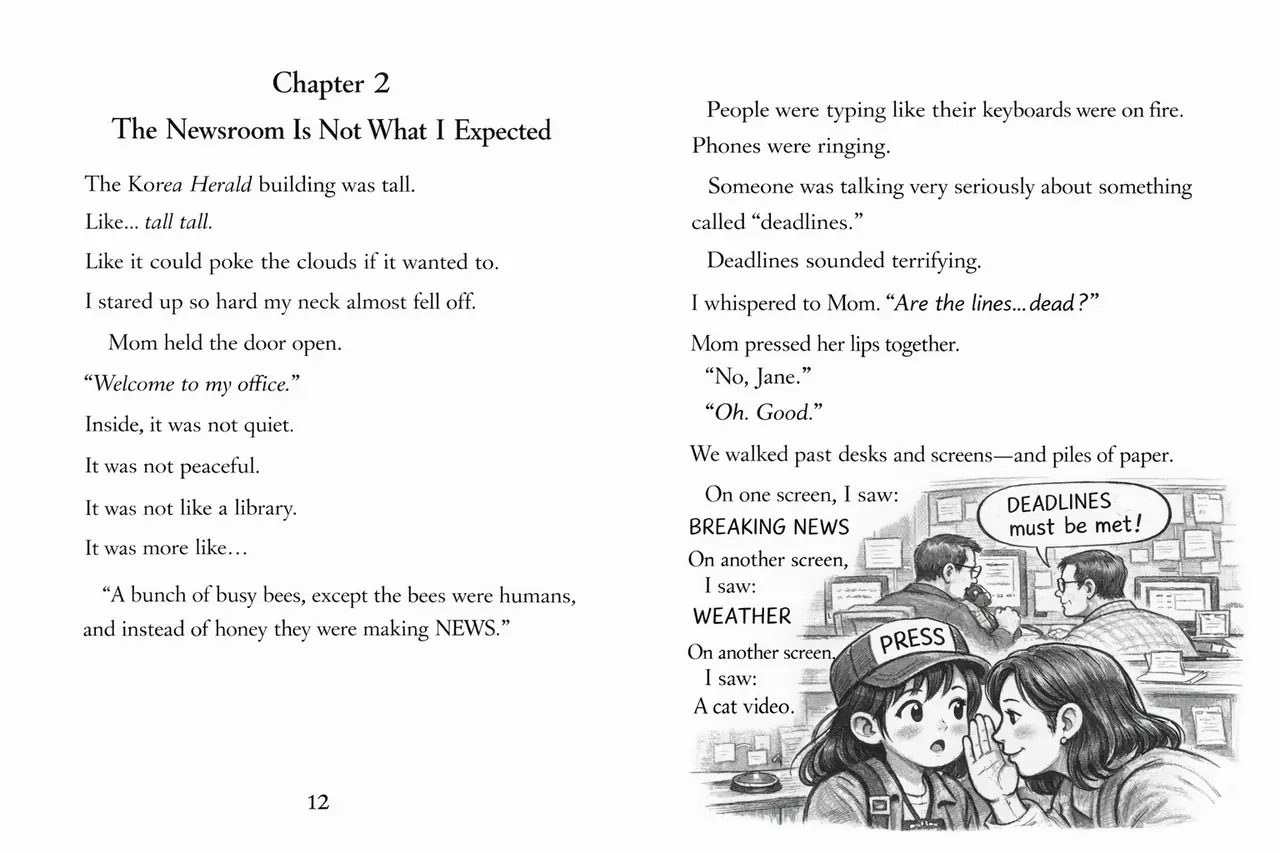

And here are a few pages from the book:

Readers can decide for themselves if the result is convincing enough to pass as something written by a human.

But this experiment shows just how quickly a book can be made with AI, something South Korea’s publishing industry is trying to cope with, for better or worse.

Publishing in the AI era

Some say AI’s rise in publishing represents a change far greater than e-publishing, even akin to the advent of movable type.

Already, the industry is seeing a surge in published titles, as AI dramatically speeds up the production process.

Last year, the National Library of Korea issued 419,534 International Standard Book Numbers, or ISBNs, a 13.5 per cent increase from 369,628 the year before.

It was the first time since records began that annual ISBN issuance posted double-digit growth, far exceeding the roughly two per cent average increase seen over the previous five years.

ISBNs are unique codes for all books published worldwide, in both print and digital formats. A big jump in ISBNs indicates more books are coming to market.

Some early local news stories have called this increase an opportunity. The idea is that if you have a good idea but lack the writing skills, AI could help level the playing field.

In early January, the Korean news outlet Edaily reported that homemakers and even high school students have published books using AI tools.

Seo Jin, CEO of Snowfox Publishing, also said that AI is giving writers new opportunities. Snowfox Publishing released Korea’s first book made with ChatGPT, called “45 ways to find the purpose of life (unofficial title).”

“For aspiring authors, this is an exceptionally strong opportunity for publishing,” she said.

Seo also said that AI use has caused a big increase in manuscript submissions. She explained that this is especially important for small publishers, who have often struggled to get enough good material.

But this boom has also revealed some problems.

A wave of low-quality books, many made with little editing, is now entering the market.

This trend is mostly driven by the search for government subsidies and quick sales.

In Korea, all books issued an ISBN must be submitted to both the National Library of Korea and the National Assembly Library. The system is designed to preserve published works as part of the nation’s documentary heritage. Publishers are required to submit two copies of each title, with libraries compensating them for the price of one.

Recently, there have been growing worries that some publishers are taking advantage of this system by putting out books that don’t even meet basic standards, like proper grammar and spelling, just to get compensation.

On February 9, the National Library of Korea said it had rejected 395 e-books from Luminary Books, submitted between July and September last year, because they were too short, reused public materials, or had repetitive content. The publisher is known for mass-producing e-books and openly using artificial intelligence in its writing and publishing.

However, publishers say this problem goes far beyond just one company, and more people are starting to worry.

“There is a group chat of roughly 2,000 publishers. Editors regularly share cases of authors submitting manuscripts that are largely completed with the help of AI,” Choi Ah-young, CEO of Calm Down Library, an independent publishing house, said.

She also gave more details about how this is hurting the local publishing industry.

“Editors sign (a contract) with authors because they value their ideas,” she said. “But when unverified information created through AI is turned into a manuscript, it creates serious trouble with fact-checking. Some manuscripts are sent back and revised, but others cannot even do that because the author never had the ability to write the book in the first place.”

She said the issue has even affected international rights deals.

“Some foreign publishers now include clauses explicitly prohibiting the use of AI for translation,” she said.

However, some people see this change as temporary and also as an opportunity.

Seo, CEO of Snowfox Publishing, is among those who view it as a chance for publishers and editors.

She believes that as more low-quality books appear, readers will become more selective. In the end, this will benefit publishers who focus on good editing and strong author voices.

“(Readers) will ask for something more than what they can get by asking ChatGPT. And that creates space for publishers who know what they are doing.”

At her company, editors are encouraged to use AI for tasks like proofreading and finding repetition or structural issues.

“This supports the editing process but doesn’t replace it,” she added.

This article was originally published on The Korea Herald, an ANN partner of Dawn. Header image via Pixabay.