TRIBUTE: EXPLAINING BANGLADESH

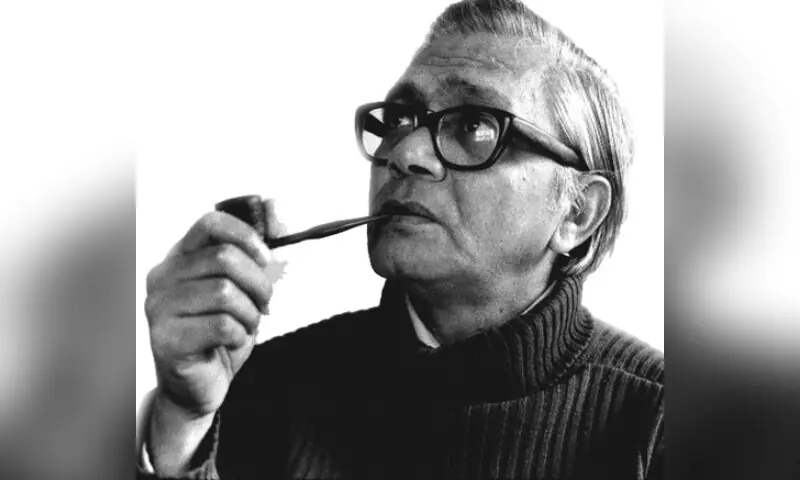

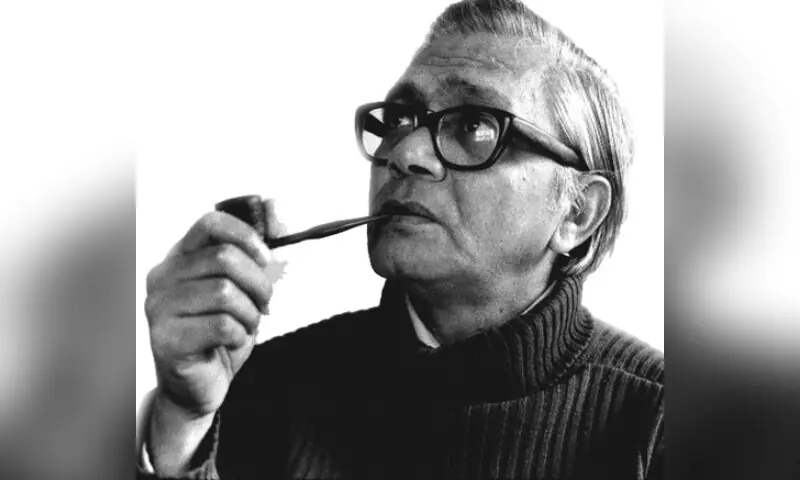

Badruddin Umar, who died in Dhaka on September 7, 2025, at the age of 93, was often introduced as a Marxist theorist and a figure of the Bangladeshi left. That label never captured the real centre of gravity of his life’s work. His lasting contribution was scholarly.

Umar left behind a meticulous body of English-language writing and translated work that gave international readers an empirically grounded view of East Bengal’s history, culture and class formation. The best of his English books and essays are neither slogans nor memoirs; they are archives in prose — dense with references, patient with evidence and consciously written to carry Bangladesh’s history beyond the limits of a single language community.

For students of South Asia who read him first in English, Umar appears primarily as a historian of structures, a cartographer of class conflict and a translator who understood translation as an intellectual act.

In the notice of his passing, Bangladeshi outlets described him as a public intellectual, researcher and teacher. These are apt terms but, to readers abroad, he is inseparable from the project of explaining East Pakistan and Bangladesh to the outside world, in the language that academic debates now most often use.

Bangladesh intellectual Badruddin Umar, who passed away in September, was often dubbed a leftist theorist. But his real legacy is scholarly: one that gives international readers an empirically grounded view of the country’s contested past

BEYOND NATIONALIST NARRATIVES

The clearest portal into Umar’s English-language corpus is his two-volume study, published by Oxford University Press. The Emergence of Bangladesh, subtitled Class Struggles in East Pakistan 1947–1958, reconstructs the first post-Partition decade through newspapers, election records, union minutes, memoirs and government papers. It is a historian’s book with a sociologist’s questions. What kinds of class coalitions formed in East Bengal? How were their interests translated into the idioms of language, region and religion? How did policy and police shape the boundaries of legitimate dissent?

Umar’s answer is pointed and empirical. He argues that the story has too often been told as a quarrel between two geographic “wings”, when the decisive conflicts were closer to the ground — in fields, mills and universities.

The companion volume, The Emergence of Bangladesh Vol 2: Rise of Bengali Nationalism 1958–1971, resumes the story under martial law and follows it into the crowded politics of the sixties. It discusses contested agrarian change, the maturing of a Bengali middle class, and the growth of an oppositional public sphere, in which language, culture and class converged.

If Volume 1 is a ledger of struggles that the state could still contain, Volume 2 is a chronicle of why it ultimately could not. In both volumes, Umar’s voice is quietly polemical. He is sceptical of narratives that flatten class antagonisms into regional grievances. One early passage challenges the fashionable mid-century talk of “disparity” between the two wings by insisting that the real divisions lay elsewhere. It is an analytic move, taking terms of nationalism and turning them back towards class.

In Volume 1, he tracks the ‘Language Movement’ through the strikes, demonstrations and pamphleteering that gave it organisational form. What is striking is not just the detail but the care with which peasant and worker experiences are interpolated into a story that could easily have been told only as a tale of student leaders and capital-city eloquence.

Because scholars outside Bangladesh often encounter him first in English, Umar’s journal essays matter as much as his books. In the late 1990s, he wrote a cluster of interventions for Economic & Political Weekly in Mumbai — pieces with titles that still circulate on reading lists. ‘Bangladesh: Intellectuals, Culture and Ruling Class’, ‘Peace in the Hills’, and ‘The Anti-Heroes of the Language Movement’ are just a couple of examples. These are less archival than the Oxford volumes but no less revealing of his method.

In interviews, he would say, in substance, that writing across languages unsettled the hierarchy between a metropolitan centre and a linguistic periphery. This is consistent with the stance one finds in his essays: cultural politics is never just about symbols; it is about the channels through which knowledge is distributed and the audiences that are imagined or excluded.

In English newspapers and magazines, he sometimes wrote with a sharper edge. One line of criticism that has been remembered, and sometimes misunderstood for its severity, is his description of Bangladesh’s early constitutional settlement as “a constitution for perpetual emergency.”

The phrase is aphoristic but it is not casual; it distils an argument he made across several pieces about the retention of colonial instruments of rule and the concentration of executive power. It is the kind of line that was born to be misquoted and, yet, its survival in public memory says something about the role he played in English-language discourse.

What makes Umar unusual among South Asian intellectuals of his cohort is that he did institution-building in both senses: he founded departments at the University of Rajshahi and he also built the paper institutions — the bibliographies, chronologies and typologies — on which later study depends.

Because he wrote for international journals and because the Oxford books became standard shelf items in university libraries, Umar’s English voice shaped how non-Bangladeshi readers understand key episodes: the 1952 Language Movement, the fall of the Muslim League in East Bengal, the trade-union reorganisation after Partition, the United Front election of 1954, the many internal arguments of the 1960s.

In The Emergence of Bangladesh, for example, he annotates the teachers’ strikes, peasant conferences and district-level by-elections that do not usually survive the drift of memory. One cannot write in English of the origins of the National Awami Party without encountering Umar’s citations and then the records to which they point.

A SOCIOLOGY OF READING

In the end, Umar knew that scholarship is also a sociology of reading. He understood that writing in English gave Bangladesh a seat at a certain table — one that did not always hear Bangla, however loudly it was spoken.

If there is a single place to begin for readers who want to meet Umar in English, it is still The Emergence of Bangladesh. Start with the early chapters where he dissects 1947; watch how he connects Partition’s arithmetic to the sociology of who was counted. Then read his reconstruction of the Language Movement through the testimony of teachers and students.

The familiar slogans are there, but the analysis lifts them off the banner and tests them against pay scales, by-laws and minutes. Then move to the 1960s and see how a vocabulary of class keeps reappearing beneath the talk of national destiny.

Badruddin Umar will be remembered as a writer whose English works gave Bangladesh a durable presence in a wider scholarly conversation, and as a translator whose ethical premise was simple: that ideas should travel both ways.

The writer is a columnist, educator and film critic. He can be contacted at mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk.

X: @NaazirMahmood

Published in Dawn, EOS, November 23rd, 2025